Point Estimation

Point estimation is an estimation to provide the single best prediction of some quantity of interest. The quantity of interest might be a single parameter or a vector of parameters such as weights but it can also be a function.

It’s a convention to denote a point estimate of a paramter \(\theta\) by \(\hat{\theta}\).

Point Estimator (statistic)

Suppose \(\{x^{(1)},..., x^{(m)}\}\) is a set of \(m\) independent and identically distributed data points. Then, a point estimator or statistic is any function of the data:

\[\hat{\theta}\_m = g(x^{(1)},...,x^{(m)})\]This definition is loose that it does not require that \(g\) return a value close to the true \(\theta\). Since the definition is general, it offers the designer of an estimator great flexibility. While any function can be an estimator, a good estimator is a function whose output is close to the true underlying \(\theta\) that generated the training data.

For now, we take the frequentist perspective on statistics. We assume that the true parameter value \(\theta\) is fixed but unknown, while the point estimate \(\hat{\theta} is a function of the data\). Since the data is drawn from a random process, any function of the data is random. Therefore, \(\hat{\theta}\) is a random variable.

Function Estimator

Point estimation can also be interpreted as the estimation of the relationship or mapping between input and target variables. We refer to these types of point estimates as function estimators.

Bias

The bias of an estimator is defined as

\[bias(\hat{\theta}\_m) = \mathbb{E}(\hat{\theta}\_m) - \theta\]where the expectation is over the data and \(\theta\) is the true underlying value of \(\theta\) used to define the data-generating distribution.

Unbiased Estimator

An estimator \(\hat{\theta}\_m\) is said to be unbiased if \(bias(\hat{\theta}_m)=0\) which implies that \(\mathbb{E}(\hat{\theta}_m)=\theta\). An estimator \(\hat{\theta}\_m\) is said to be asymptotically unbiased if \(\lim\_{m \rightarrow \infty} \mathbb{E}(\hat{\theta}\_m)=\theta\).

Example: Bernoulli Distribution

Consider a set of samples \(\{ x^{(1)},...,x^{(m)} \}\) that are independently and identically distributed according to a Bernoulli distribution with mean \(\theta\):

\[P(x^{(i)}; \theta) = \theta^{x^{(i)}}(1-\theta)^{(1-x^{(i)})}\]A common estimator for the \(\theta\) parameter of this distribution is the mean of the training samples:

\[\hat{\theta}\_m = \frac{1}{m} \sum]\_{i=1}^m x^{(i)}\]Let’s see if this estimator is biased or unbiased.

\[bias(\hat{\theta}\_m) = \mathbb{E}(\hat{\theta}\_m) - \theta\] \[= \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m x^{(i)} \right] - \theta\] \[= \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m \mathbb{E} \left[ x^{(i)} \right] - \theta\] \[= \frac{1}{m} \sum*{i=1}^m \sum*{x^{(i)}}^1 \left( x^{(i)}\theta^{x^{(i)}}(1-\theta)^{(1-x^{(i)})} \right) - \theta\] \[= \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m (\theta) - \theta\] \[= \theta - \theta\] \[=0\]Since we showed \(bias(\hat{\theta})=0\), the estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) is unbiased.

Example: Estimator of Gaussian Distribution Mean

Consider a set of samples \(\{ x^{(1)},...,x^{(m)} \}\) that are independently and identically distributed according to a Gaussian distribution \(p(x^{(i)}) = \mathcal{N}(x^{(i)}; \mu, \sigma^2)\), where \(i \in \{ 1, ..., m \}\). The Gaussian probability density function is given by,

\[p(x^{(i)}; \mu, \sigma^2) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \pi \sigma^2}}exp \left( -\frac{1}{2} \frac{(x^{(i)}-\mu)^2}{\sigma^2} \right)\]A common estimator of the Gaussian mean parameter is the sample mean:

\[\hat{\mu}\_m = \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m x^{(i)}\]Let’s find out the bias of this estimator,

\[bias(\hat{\mu}\_m) = \mathbb{E}[\hat{\mu}_m] - \mu\] \[= \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m x^{(i)} \right] - \mu\] \[= \left( \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m \mathbb{E}[x^{(i)}] \right) - \mu\] \[= \left( \frac{1}{m} \sum\_{i=1}^m \mu \right) - \mu\] \[\mu - \mu = 0\]Thus, we showed that the sample mean is an unbiased estimator of Gaussian mean parameter \(\mu\).

Example: Estimators of Gaussian Distribution Variance

Let’s now look Let’s compare two different estimators of the variance parameter \(\sigma^2\) of a Gaussian Distribution.

The first estimator of \(\sigma^2\) is the sample variance:

\[\hat{\sigma}\_m^2 = \frac{1}{m}\sum\_{i=1}^m \left( x^{(i)} - \hat{\mu}\_m \right)^2\]where \(\hat{\mu}\_m\) is the sample mean. To find the bias,

\[bias(\hat{\sigma}\_m^2) = \mathbb{E}[\hat{\sigma}_m^2] - \sigma^2\] \[= \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{1}{m} \sum_{i=1}^m (x^{(i)} - \hat{\mu}_m)^2 \right] - \sigma^2\] \[= \frac{m-1}{m} \sigma^2 - \sigma^2\]Since the bias is non-zero, the sample mean is a biased estimator of the variance.

Instead, let’s consider the estimator,

\[\tilde{\sigma}\_m^2 = \frac{1}{m-1} \sum\_{i=1}^m \left( x^{(i)} - \hat{\mu}\_m \right)^2\]Then,

\[bias(\hat{\sigma}\_m^2) = \mathbb{E}[\hat{\sigma}_m^2] - \sigma^2\] \[= \mathbb{E} \left[ \frac{1}{m-1} \sum_{i=1}^m (x^{(i)} - \hat{\mu}_m)^2 \right] - \sigma^2\] \[= \frac{m}{m-1} \mathbb{E}[\tilde{\sigma}_m^2] - \sigma^2\] \[= \frac{m}{m-1} (\frac{m-1}{m}\sigma^2) - \sigma^2\] \[= 0\]Therefore, we conclude that this is the unbiased estimator for the variance.

Variance and Standard Error

The variance of an estimator is simply the variance

\[Var(\hat{\theta})\]where the random variable is the training set. The square root of the variance is called the standard error, denoted \(SE(\hat{\theta})\).

The variance or the standard error provides a measure of how we expect the estimate we compute from the data vary as we independently resample the dataset from the underlying data-generating process. Just like we compute an estimator to have low bias, we also want it to have low variance.

When we compute any statistic using a finite number of samples, the estimate would mostly not be equal to the true parameter. The expected degree of variation in any estimator is a source of error that we want to quantify.

The standard error of the mean is given by

\[S(\hat{\mu}\_m) = \sqrt{Var \left[ \frac{1}{m}\sum\_{i=1}^m x^{(i)} \right]} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{m}}\]where \(\sigma^2\) is the true variance of the samples \(x^i\).

Trading off Bias and Variance to minimize MSE

Bias and Variance offers us two different sources of error in an estimator. Bias measures the expected deviation from the true value of the function or parameter. Variance measures the deviation from the expected estimator value.

But how do we make decisions between two estimators, one with large bias and one with large variance? The most common way to negotiate this trade-off is to use cross-validatioin. Alternatively, we can also compare the mean squared error (MSE) of the estimates.

\[MSE = \mathbb{E}[(\hat{\theta}_m - \theta)^2]\] \[= Var(\hat{\theta}\_m - \theta) + (\mathbb{E}[\hat{\theta}_m - \theta])^2,\ \because Var(X)=\mathbb{E}[X^2]-\mathbb{E}[X]^2\] \[= Var(\hat{\theta}\_m) + Bias^2(\hat{\theta_m})\]The MSE measures the overall expected deviation between the estimator and the true value of the parameter \(\theta\). From the equation, we see that the MSE incorporates both the bias and the variance. Desirable estimators manage to have small MSE, balancing both the variance and the bias.

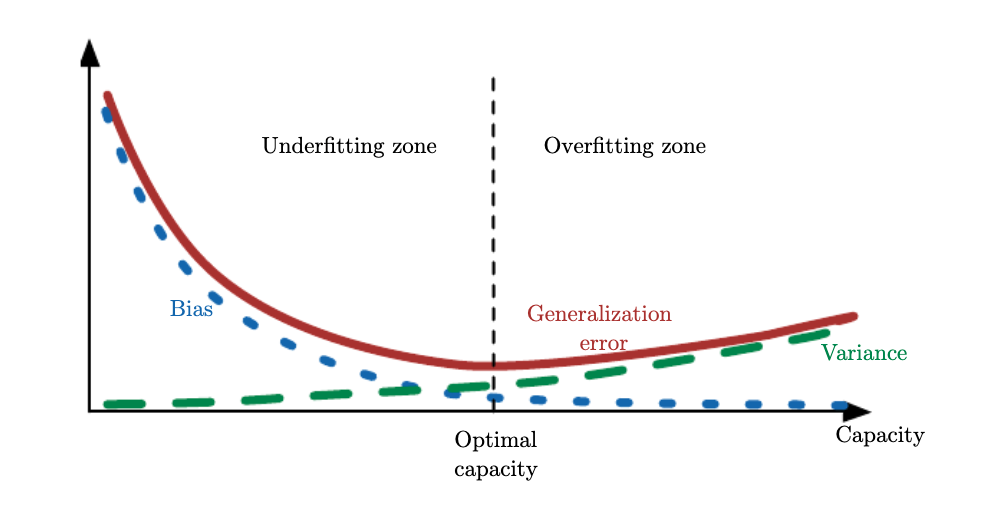

The relationship between the bias and the variance is tightly connected to the machine learning concepts of capacity, underfitting, and overfitting.

When the generalization error is measured by the MSE, increasing capacity tends to increase variance and decrease bias.

Consistency

So far, we have talked about the properties of estimator for a fixed training set. But what happens as the training data grows? We usually wish that as the training size grows, our point estimates converge to the true value of the corresponding parameters. Formally, we would like that

\[plim\_{m \rightarrow \infty} \hat{\theta}\_m = \theta\]The symbol \(plim\) indicates convergence in probability, meaning that for any \(\epsilon > 0, P(\lvert \hat{\theta}_m - \theta \rvert > \epsilon)\) as \(m \rightarrow \infty\). This is sometimes referred to as weak consistency. The strong consistency refers to the “almost sure” convergence of \(\hat{\theta}\) to \(\theta\).

Consistency ensures that the bias induced by the estimator diminishes as the number of data grows. However, the reverse is not true - asymptotic unbiasedness does not imply consistency.

References